Chapter 8: Starting the SimpleSite Tutorial

Note

You can download the source code for this chapter from http://www.apress.com.

You’ve now learned about many of the most important components of an application. The previous chapters have been fairly detailed, so don’t worry if you haven’t understood everything you’ve read or if you’ve skipped over one or two sections. Once you have used Pylons a little more, you will appreciate having all the information on a particular topic in one place, even if it seems a lot to take in on the first reading.

In this chapter, I’ll recap many of the important points as I show how to create a simple web site from scratch so that you can see how all the components you’ve learned about in the preceding chapters fit together. The example will be created in a way that will also make it a really good basis for your own Pylons projects.

You’ll use SQLAlchemy to store the individual pages in the site in such a way that users can add, edit, or remove them so that the application behaves like a simple wiki. Each of the pages will also support comments and tags, so you can use some of the knowledge gained in the previous chapter to help you create the application. You’ll also use FormEncode and HTML Fill to handle the forms.

Later in the book you’ll return to SimpleSite and add authentication and authorization facilities, and you’ll add a navigation hierarchy so that pages can be grouped into sections at different URLs. You’ll implement some JavaScript to animate messages and use some Ajax to populate one of the form fields. The application will also have a navigation hierarchy so that you can see how to create navigation components such as breadcrumbs, tabs, and navigation menus using Mako.

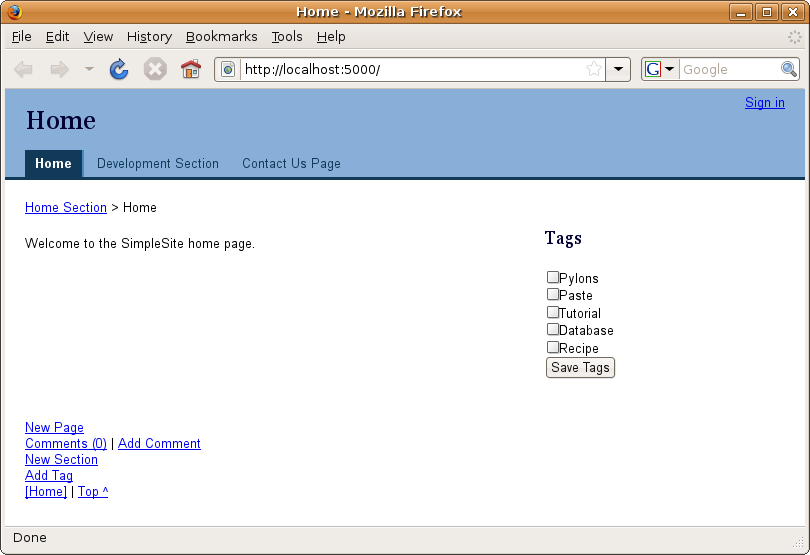

Figure 8-1 shows what the finished application will look like after the SimpleSite tutorial chapters (this chapter, Chapter 14, part of Chapter 15, and Chapter 19).

Getting Started with SimpleSite

The first thing you need to do is create a new Pylons project called SimpleSite. You’ll remember from Chapter 3 that the command to do this is as follows:

$ paster create --template=pylons SimpleSite

You’ll use Mako and SQLAlchemy in this chapter, so in particular note that you need to answer True to the SQLAlchemy question so that SQLAlchemy support is included for you:

Selected and implied templates: Pylons#pylons Pylons application template Variables: egg: SimpleSite package: simplesite project: SimpleSite Enter template_engine (mako/genshi/jinja/etc: Template language) ['mako']: Enter sqlalchemy (True/False: Include SQLAlchemy 0.4 configuration) [False]: True Creating template pylons

All these options are configurable later, but it is easier to have Pylons configure them for you when you create the project.

Once the application template has been created, start the server, and see what you have:

$ cd SimpleSite $ paster serve --reload development.ini

Note

Notice that the server is started with the --reload switch. You’ll remember that this means any changes you make to the code will cause the server to restart so that your changes are immediately available for you to test in the web browser.

If you visit http://127.0.0.1:5000, you will see the standard Pylons introduction page served from the application’s public/index.html file as before.

Pylons looks for resources in the order applications are specified in the cascade object in config/middleware.py. You’ll learn more about the cascade object in Chapter 17, but it causes static files such as the introduction page to be served in preference to content generated by your Pylons controllers for the same URL. You will want the SimpleSite controllers to handle the site’s home page, so remove the welcome page HTML file:

$ cd simplesite $ rm public/index.html

If you now refresh the page, the Pylons built-in error document support will kick in and display a 404 Not Found page to tell you that the URL requested could not be matched by Pylons.

You’ll now customize the controller so that it can display pages. Each of the pages is going to have its own ID, which the controller will obtain from the URL. Here are some example URLs that the controller will handle:

/page/view/1 /page/view/2 ... etc /page/view/10

You’ll also recall that Pylons comes with a routing system named Routes, which you saw in Chapter 3 and will learn about in detail in the next chapter. The default Routes setup analyzes the URL requested by the browser to find the controller, action, and ID. This means that to handle the URLs, you simply need a controller named page that has an action named view and that takes a parameter named id.

Let’s create the page controller. Once again, Pylons comes with a tool to help with this in the form of a plug-in to Paste. You create the controller like this (notice that the command doesn’t include the create part, which is used when creating a project template):

$ paster controller page Creating /Users/james/Desktop/SimpleSite/simplesite/controllers/page.py Creating /Users/james/Desktop/SimpleSite/simplesite/tests/functional/test_page.py

This creates two files—one for any tests you are going to add for this controller (see Chapter 12) and the other for the controller itself. The command would also add these files to Subversion automatically if your Pylons application were already being managed in a Subversion repository.

The controllers/page.py file that is added looks like this:

import logging

from pylons import request, response, session, tmpl_context as c

from pylons.controllers.util import abort, redirect_to

from simplesite.lib.base import BaseController, render

#import simplesite.model as model

log = logging.getLogger(__name__)

class PageController(BaseController):

def index(self):

# Return a rendered template

# return render('/template.mako')

# or, Return a response

return 'Hello World'

This is a skeleton controller that you’ll customize to handle pages. The first few lines import some of the useful objects described in Chapter 3 so that they are ready for you to use. The controller itself has one action named index(), which simply returns a Hello World message.

Replace the index() action with a view() action that looks like this:

def view(self, id):

return "Page goes here"

The Paste HTTP server should reload when you save the change (as long as you used the --reload option), so you can now visit the URL http://localhost:5000/page/view/1. You should see the message Page goes here.

The page isn’t very exciting so far and isn’t even HTML, so now I’ll cover how to create some templates to generate real HTML pages.

Exploring the Template Structure

Most web sites have the following features:

Header and footer regions

Sign-in and sign-out regions

Top-level navigation tabs

Second-level navigation tabs

A page heading

Breadcrumbs

Content

A head region for extra CSS and JavaScript

The SimpleSite application will need all these features too, so the template structure needs to be able to provide them.

You’ll remember from Chapter 5 that Pylons uses the Mako templating language by default, although as is the case with most aspects of Pylons, you are free to deviate from the default if you prefer. This is particularly useful if you are building a Pylons application to integrate with legacy code, but since you are creating a new application here, you are going to use Mako.

Because you are going to need a few templates that will all look similar, you can take advantage of Mako’s inheritance chain features you learned about in Chapter 5 and use a single base template for all the different pages. You’ll also need to create some derived templates and some templates containing the navigation components.

You’ll structure these templates as follows:

- templates/base

All the base templates.

- templates/derived

All the templates that are derived from any of the base templates. There is likely to be a subdirectory for every controller you create. Since Pylons has already created an error controller, you’ll create a subdirectory for it, and you’ll need a subdirectory for the page controller templates too.

- templates/derived/error

Templates for the error controller to render error documents.

- templates/component

Any components that are used in multiple templates.

This structure is useful because it keeps templates that serve different purposes in different directories. If you are following along by creating the application yourself, you should create these directories now.

Let’s start by creating the base template. Save the following template as templates/base/index.html:

## -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<title>${self.title()}</title>

${self.head()}

</head>

<body>

${self.header()}

${self.tabs()}

${self.menu()}

${self.heading()}

${self.breadcrumbs()}

${next.body()}

${self.footer()}

</body>

</html>

<%def name="title()">SimpleSite</%def>

<%def name="head()"></%def>

<%def name="header()"><a name="top"></a></%def>

<%def name="tabs()"></%def>

<%def name="menu()"></%def>

<%def name="heading()"><h1>${c.heading or 'No Title'}</h1></%def>

<%def name="breadcrumbs()"></%def>

<%def name="footer()"><p><a href="#top">Top ^</a></p></%def>

This template should be fairly self-explanatory. It is a simple HTML document with eight defs defined. Each of the calls to ${self.somedef()} will execute the def using either the definition in this base template or the definition in the template that inherits from it. The ${next.body()} call will be replaced with the body of the template that inherits this one.

You’ll also see that the header() and footer() defs already contain some HTML, allowing the user to quickly click to the top of the page. The title() def contains some code that will set the title to SimpleSite, and the heading() def will obtain its content from the value of c.heading or will just use 'No title' if no heading has been set.

## -*- coding: utf-8 -*- has been added at the top of the file so that Unicode characters can be used when the template is saved as UTF-8 (you’ll learn more about Unicode in Chapter 10).

Note

If you prefer using the strict_c option to ensure that accessing an attribute of the template context global raises an exception if that attribute doesn’t exist, you should change the content of the heading def to look like this:

<h1>${hasattr(c, 'heading') and c.heading or 'No Title'}</h1>

This ensures that the heading attribute exists before testing its value.

Now that the base template is in place, you can start creating the templates for the web site content. Create a new template in the templates/derived/page directory called view.html. This will be the template used by the page controller’s view action. Add the following content to it:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html"/>

${c.content}

You’ll now need to update the view() action in the controller to use this template:

def view(self, id):

c.title = 'Greetings'

c.heading = 'Sample Page'

c.content = "This is page %s"%id

return render('/derived/page/view.html')

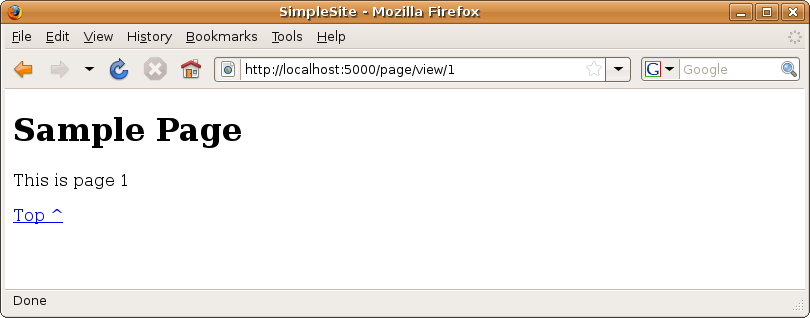

Now when you visit http://localhost:5000/page/view/1, you should see the page shown in Figure 8-2.

Using SQLAlchemy in Pylons

Now that you have the project’s templates and controller set up, you need to start thinking about the model. As you’ll recall from Chapter 1, Pylons is set up to use a Model View Controller architecture, and SQLAlchemy is what is most often used as the model. Chapter 7 explained SQLAlchemy in detail, but now you’ll see how to apply that theory to a real Pylons project. If you haven't already done so you'll need to install SQLAlchemy 0.5 which is the version used in this book. You can do so with this command:

$ easy_install "SQLAlchemy>=0.5,<=0.5.99"

Let’s begin by setting up the engine. Open your project’s config/environment.py file, and after from pylons import config, you’ll see the following:

from sqlalchemy import engine_from_config

You learned about engines in Chapter 7 when you created one directly. Pylons uses the engine_from_config() function to create an engine from configuration options in your project’s config file instead. It looks for any options starting with sqlalchemy. in the [app:main] section of your development.ini config file and creates the engine based on these options. This means that all you need to do to configure SQLAlchemy is set the correct options in the config file.

Configuring the Engine

The main configuration option you need is sqlalchemy.url. This specifies the data source name (DSN) for your database and takes the format engine://username:password@host:port/database?foo=bar, where foo=bar sets an engine-specific argument named foo with the value bar. Once again, this is the same setting you learned about in Chapter 7 during the discussion of engines.

For SQLite, you might use an option like this to specify a database in the same directory as the config file:

sqlalchemy.url = sqlite:///%(here)s/databasefile.sqlite

Here databasefile.sqlite is the SQLite database file, and %(here)s represents the directory containing the development.ini file. If you’re using an absolute path, use four slashes after the colon: sqlite:////var/lib/myapp/databasefile.sqlite. The example has three slashes because the value of %(here)s always starts with a slash on Unix-like platforms. Windows users should use four slashes because %(here)s on Windows starts with the drive letter.

For MySQL, you might use these options:

sqlalchemy.url = mysql://username:password@host:port/database sqlalchemy.pool_recycle = 3600

Enter your username, your password, the host, the port number (usually 3306), and the name of your database.

It’s important to set the pool_recycle option for MySQL to prevent “MySQL server has gone away” errors. This is because MySQL automatically closes idle database connections without informing the application. Setting the connection lifetime to 3600 seconds (1 hour) ensures that the connections will be expired and re-created before MySQL notices they’re idle. pool_recycle is one of many engine options SQLAlchemy supports. Some of the others are listed at http://www.sqlalchemy.org/docs/05/dbengine.html#dbengine_options and are used in the same way, prefixing the option name with sqlalchemy..

For PostgreSQL, your DSN will usually look like this:

sqlalchemy.url = postgres://username:password@host:port/database

The options are the same as for MySQL, but you don’t generally need to use the pool_recycle option with PostgreSQL.

By default, Pylons sets up the DSN sqlalchemy.url = sqlite:///%(here)s/development.db, so if you don’t change it, this is what will be used. Whichever DSN you use, you still need to make sure you have installed SQLAlchemy along with the appropriate DB-API driver you want to use; otherwise, SQLAlchemy won’t be able to connect to the database. Again, see Chapter 7 for more information.

Creating the Model

Once you have configured the engine, it is time to configure the model. This is easy to do; you simply add all your classes, tables, and mappers to the end of model/__init__.py. The SimpleSite application will use the structures you worked through in the previous chapter, so I won’t discuss them in detail here.

Change model.__init__.py to look like this:

"""The application's model objects"""

import sqlalchemy as sa

from sqlalchemy import orm

from simplesite.model import meta

# Add these two imports:

import datetime

from sqlalchemy import schema, types

def init_model(engine):

"""Call me before using any of the tables or classes in the model"""

## Reflected tables must be defined and mapped here

#global reflected_table

#reflected_table = sa.Table("Reflected", meta.metadata, autoload=True,

# autoload_with=engine)

#orm.mapper(Reflected, reflected_table)

# We are using SQLAlchemy 0.5 so transactional=True is replaced by

# autocommit=False

sm = orm.sessionmaker(autoflush=True, autocommit=False, bind=engine)

meta.engine = engine

meta.Session = orm.scoped_session(sm)

# Replace the rest of the file with the model objects we created in

# chapter 7

def now():

return datetime.datetime.now()

page_table = schema.Table('page', meta.metadata,

schema.Column('id', types.Integer,

schema.Sequence('page_seq_id', optional=True), primary_key=True),

schema.Column('content', types.Text(), nullable=False),

schema.Column('posted', types.DateTime(), default=now),

schema.Column('title', types.Unicode(255), default=u'Untitled Page'),

schema.Column('heading', types.Unicode(255)),

)

comment_table = schema.Table('comment', meta.metadata,

schema.Column('id', types.Integer,

schema.Sequence('comment_seq_id', optional=True), primary_key=True),

schema.Column('pageid', types.Integer,

schema.ForeignKey('page.id'), nullable=False),

schema.Column('content', types.Text(), default=u''),

schema.Column('name', types.Unicode(255)),

schema.Column('email', types.Unicode(255), nullable=False),

schema.Column('created', types.TIMESTAMP(), default=now()),

)

pagetag_table = schema.Table('pagetag', meta.metadata,

schema.Column('id', types.Integer,

schema.Sequence('pagetag_seq_id', optional=True), primary_key=True),

schema.Column('pageid', types.Integer, schema.ForeignKey('page.id')),

schema.Column('tagid', types.Integer, schema.ForeignKey('tag.id')),

)

tag_table = schema.Table('tag', meta.metadata,

schema.Column('id', types.Integer,

schema.Sequence('tag_seq_id', optional=True), primary_key=True),

schema.Column('name', types.Unicode(20), nullable=False, unique=True),

)

class Page(object):

pass

class Comment(object):

pass

class Tag(object):

pass

orm.mapper(Comment, comment_table)

orm.mapper(Tag, tag_table)

orm.mapper(Page, page_table, properties={

'comments':orm.relation(Comment, backref='page'),

'tags':orm.relation(Tag, secondary=pagetag_table)

})

Warning

The book was written against Pylons 0.9.7rc2 but the actual release of Pylons 0.9.7 uses SQLAlchemy 0.5 by default. This means the init_model() function in your project might look slightly different to the version shown above. You should keep the version generated by Pylons rather than using the version above. In Pylons 0.9.7 the sessionmaker() call is still made, but it happens in your project's model/meta.py file instead of model/__init__.py.

As I mentioned, this will look very familiar because it is a similar setup to the one you used in the previous chapter. There are some points to note about this code, though:

The MetaData object Pylons uses is defined in model/meta.py so is accessed here as meta.metadata, whereas in the previous chapter the examples just used metadata.

Pylons generated the init_model() function when the project was created. It gets called after the engine has been created each time your application starts from config/environment.py to connect the model to the database.

Caution!

Pylons generates a project to use SQLAlchemy 0.4, but many users will want to use the newer SQLAlchemy 0.5 described in Chapter 7. They are very similar, but the transactional=True argument to orm.sessionmaker() in init_model() is deprecated. Instead, you should specify autocommit=False. This has the same behavior but will not generate a deprecation warning.

Creating the Database Tables

Pylons has a built-in facility to allow users who download your application to easily set it up. The process is described in detail in the later SimpleSite tutorial chapters (Chapters 14 and 19), but you’ll use it here too so that you can easily set up the tables you need.

The idea is that users of your application can simply run paster setup-app development.ini to have the database tables and any initial data created for them automatically. You can set up this facility through your project’s websetup.py file.

The default websetup.py file for a SQLAlchemy project looks like this:

"""Setup the SimpleSite application"""

import logging

from simplesite.config.environment import load_environment

log = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def setup_app(command, conf, vars):

"""Place any commands to setup simplesite here"""

load_environment(conf.global_conf, conf.local_conf)

# Load the models

from simplesite.model import meta

meta.metadata.bind = meta.engine

# Create the tables if they aren't there already

meta.metadata.create_all(checkfirst=True)

When the paster setup-app command is run, Pylons calls the setup_app() function and loads the Pylons environment, setting up a SQLAlchemy engine as it does so. It then binds the engine to the metadata and calls metadata.create_all(checkfirst=True) to create any tables that don’t already exist.

Binding the metadata in this way connects the engine to the metadata object used by the classes, tables, and mappers in the model. You can think of it as a shortcut to set up the model without the complexity of a session.

You’ll now customize the default code so that it also adds a home page to the database. Add the following to the end of the setup_app() function:

log.info("Adding homepage...")

page = model.Page()

page.title=u'Home Page'

page.content = u'Welcome to the SimpleSite home page.'

meta.Session.add(page)

meta.Session.commit()

log.info("Successfully set up.")

You’ll also need to add this import at the top:

from simplesite import model

Note

The recommended way of adding an object to the SQLAlchemy session in SQLAlchemy 0.4 was to call the session's save() method. The session in SQLAlchemy 0.5 provides the add() method instead. Since this book covers SQLAlchemy 0.5, the examples will use the add() method.

To test this functionality, you should first make SimpleSite available in your virtual Python environment. Rather than installing SimpleSite as you would install a normal Python package, you can instead use a special feature of the setuptools package used by Easy Install called development mode. This has the effect of making other Python packages treat your Pylons project’s source directory as if it were an installed Python egg even though it is actually just a directory structure in the filesystem.

It works by adding a SimpleSite.egg-link file to your virtual Python installation's site-packages directory containing the path to the application. It also adds an entry to the easy_install.pth file so that the project is added to the Python path. This is very handy because it means that any changes you make to the SimpleSite project are instantly available without you having to create and install the package every time you make a change. Set up your project in development mode by entering this command:

$ python setup.py develop

If you haven’t specified sqlalchemy.url in your development.ini config file, you should do so now. Then you are ready to run the paster setup-app command to set up your tables:

$ paster setup-app development.ini

If all goes well, you should see quite a lot of log output produced, ending with the following lines and the message that everything was successfully set up:

12:37:36,429 INFO [simplesite.websetup] Adding homepage... 12:37:36,446 INFO [sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine.0x..70] BEGIN 12:37:36,449 INFO [sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine.0x..70] INSERT INTO page (content, posted, title, heading) VALUES (?, ?, ?, ?) 12:37:36,449 INFO [sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine.0x..70] [u'Welcome to the SimpleSite home page.', '2008-09-12 12:37:36.449094', u'Home Page', None] 12:37:36,453 INFO [sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine.0x..70] COMMIT 12:37:36,460 INFO [simplesite.websetup] Successfully set up.

Querying Data

Now that the home page data is in SQLAlchemy, you need to update the view() action to use it. You’ll recall that you query SQLAlchemy using a query object. Here’s how:

def view(self, id):

page_q = model.meta.Session.query(model.Page)

c.page = page_q.get(int(id))

return render('/derived/page/view.html')

Notice that since the heading is optional, you are using the title as the heading if the heading is empty.

To use this, you need to uncomment the following line at the top of the controller file:

#import simplesite.model as model

Now add some more imports the controller will need:

import simplesite.model.meta as meta import simplesite.lib.helpers as h

Finally, you’ll need to update the templates/derived/page/view.html template to use the page object:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html"/>

<%def name="title()">${c.page.title}</%def>

<%def name="heading()"><h1>${c.page.heading or c.page.title}</h1></%def>

${c.page.content}

The new heading def will display the heading if there is one and the title if no heading has been set.

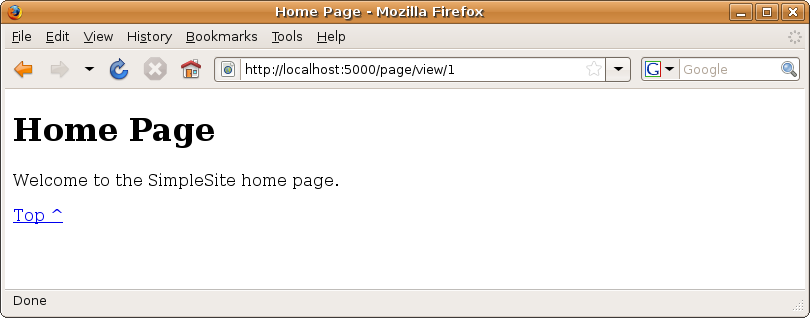

Visit http://localhost:5000/page/view/1 again, and you should see the data loaded from the database (Figure 8-3). You’ll need to restart the server if you stopped it to run paster setup-app.

Caution!

Generally speaking, it is a good idea to try to keep your model and templates as separate as possible. You should always perform all model operations in your controller and never in a template. This is so that you, and other people working on your project, always know where changes to your model are happening so that code is easy to maintain.

To avoid the risk of a lazy programmer performing operations on the model from within a template, you might prefer not to pass model objects directly to the controller and instead pass the useful attributes. In this case, rather than passing c.page, you might instead pass c.title, c.content, and other useful attributes rather than the whole object. In this book, I’ll be strict about only using model objects for read-only access in templates, so it is OK to pass them in directly.

Understanding the Role of the Base Controller

Every Pylons project has a base controller in the project’s lib/base.py file. All your project’s controllers are by default derived from the BaseController class, so this means that if you want to change the behavior of all the controllers in your project, you can make changes to the base controller. Of course, if you want to derive your controllers directly from pylons.controllers.WSGIController, you are free to do so too.

The SimpleSite base controller looks like this:

"""The base Controller API

Provides the BaseController class for subclassing.

"""

from pylons.controllers import WSGIController

from pylons.templating import render_mako as render

from simplesite.model import meta

class BaseController(WSGIController):

def __call__(self, environ, start_response):

"""Invoke the Controller"""

# WSGIController.__call__ dispatches to the Controller method

# the request is routed to. This routing information is

# available in environ['pylons.routes_dict']

try:

return WSGIController.__call__(self, environ, start_response)

finally:

meta.Session.remove()

All the individual controllers that you create with the paster controller command also import the render() function from this file, so if you want to change the templating language for all your controllers, you can change the render() import in this file, and all the other controllers will automatically use the new function. Of course, you will have to set up the templating language in your project’s config/environment.py file too. This was described in Chapter 5.

Using a SQLAlchemy Session in Pylons

You’ve learned about SQLAlchemy sessions in some detail in Chapter 7, but now let’s take a brief look at how sessions are used in Pylons.

The relevant lines to set up the session are found in your model/__init__.py file’s init_model() function and look like this:

sm = orm.sessionmaker(autoflush=True, autocommit=False, bind=engine) meta.engine = engine meta.Session = orm.scoped_session(sm)

The meta.Session class created here acts as a thread-safe wrapper around ordinary SQLAlchemy session objects so that data from one Pylons request doesn’t get mixed up with data from other requests in a multithreaded environment. Calling meta.Session() returns the thread’s actual session object, but you wouldn’t normally need to access it in this way because when you call the class’s meta.Session.query() method, it will automatically return a query object from the correct hidden session object. You can then use the query object as normal to fetch data from the database.

Since a new session is created for each request, it is important that sessions that are no longer needed are removed. Because you chose to use a SQLAlchemy setup when you created the project, Pylons has added a line to remove any SQLAlchemy session at the end of the BaseController class’s __call__() method:

meta.Session.remove()

This simply removes the session once your controller has returned the data for the response.

Updating the Controller to Support Editing Pages

To quickly recap, you’ve set up the model, configured the database engine, set up the templates, and written an action to view pages based on their IDs. Next, you need to write the application logic and create the forms to enable a user to create, list, add, edit, and delete pages.

You’ll need the following actions:

- view(self, id)

Displays a page

- new(self)

Displays a form to create a new page

- create(self)

Saves the information submitted from new() and redirects to view()

- edit(self, id)

Displays a form for editing the page id

- save(self, id)

Saves the page id and redirects to view()

- list(self)

Lists all pages

- delete(self, id)

Deletes a page

This structure forms a good basis for a large number of the cases you are likely to program with a relational database.

view()

The existing view() method correctly displays a page but currently raises an error if you try to display a page that doesn’t exist. This is because page_q.get() returns None when the page doesn't exist so that c.page is set to None. This causes an exception in the template when c.page.title is accessed.

Also, if a URL cannot be found, the HTTP specification says that a 404 page should be returned. You can use the abort() function to immediately stop the request and trigger the Pylons error documents middleware to display a 404 Not Found page. You should also display a 404 page if the user doesn’t specify a page ID. Here’s what the updated code looks like. Notice that the action arguments have been changed so that id is now optional.

def view(self, id=None):

if id is None:

abort(404)

page_q = meta.Session.query(model.Page)

c.page = page_q.get(int(id))

if c.page is None:

abort(404)

return render('/derived/page/view.html')

Tip

When you are testing a condition that involves None in Python, you should use the is operator rather than the == operator.

new()

You also need a template for pages that don’t already exist. It needs to display a form and submit it to the create() action to create the page. Most of the functionality to display the form will take place in the templates. Here’s what the action looks like; add this to the controller:

def new(self):

return render('/derived/page/new.html')

Thinking ahead, the edit() action will also display a form, and it is likely to have many of the same fields. You’ll therefore implement the fields in one template where they can be shared and create the form itself in another.

First let’s create the fields in templates/derived/page/fields.html. Here’s what the file looks like:

${h.field(

"Heading",

h.text(name='heading'),

required=False,

)}

${h.field(

"Title",

h.text(name='title'),

required=True,

field_desc = "Used as the heading too if you didn't specify one above"

)}

${h.field(

"Content",

h.textarea(name='content', rows=7, cols=40),

required=True,

field_desc = 'The text that will make up the body of the page'

)}

Remember that h is simply another name for your project’s simplesite.lib.helpers module and that it is available in both the templates and the controllers. In this case, you’re using a helper called field() that generates the HTML for a row in a table containing a label for a field and the field itself. It also allows you to specify field_desc, which is a line of text that appears immediately below the HMTL field, or label_desc, which is for text appearing immediately below the label. Specifying required=True adds an asterisk (*) to the start of the label, but it doesn’t affect how the controller handles whether fields are actually required.

To use the field helper, you need to first import it into the helpers module. You’ll also use form_start() and form_end(), so let’s import them at the same time. At the top of lib/helpers.py, add the following:

from formbuild.helpers import field from formbuild import start_with_layout as form_start, end_with_layout as form_end from webhelpers.html.tags import *

Notice that you are using a package called FormBuild here. You could equally well code all your field structures in HTML, but FormBuild will help create a structure for you. FormBuild actually contains some extra functionality too, but you will use it only for its field(), start_with_layout(), and end_with_layout() helpers in the book. At some point in the future, these helpers are likely to be added to the Pylons WebHelpers package. Install FormBuild like this:

$ easy_install "FormBuild>=2.0,<2.99"

You should also add it as a dependency to your project by editing the setup.py file and adding FormBuild to the end of the install_requires argument, and updating the SQLAlchemy line to look like this:

install_requires=[

"Pylons>=0.9.7",

"SQLAlchemy>=0.5,<=0.5.99",

"Mako",

"FormBuild>=2.0,<2.99",

],

Next you need the form itself. Like the view.html page, this can be based on the /base/index.html page using Mako’s template inheritance. Here’s how /derived/page/new.html looks:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html" />

<%namespace file="fields.html" name="fields" import="*"/>

<%def name="heading()">

<h1 class="main">Create a New Page</h1>

</%def>

${h.form_start(h.url_for(controller='page', action='create'), method="post")}

${fields.body()}

${h.field(field=h.submit(value="Create Page", name='submit'))}

${h.form_end()}

This template imports the defs in the fields.html file into the fields namespace. It then calls its body() def to render the form fields. h.form_start() and h.form_end() create the HTML <form> tags as well as the <table> tags needed to wrap the rows generated by each call to h.field().

You’ll also need to add the url_for() helper to lib/helpers.py. This is a function from Routes that you’ll learn about in Chapter 9. For the time being, it is enough to know that it takes a controller, action, and ID and will generate a URL that, when visited, will result in the controller and action being called with the ID you specified. Routes is highly customizable and is one of the central components Pylons provides to make building sophisticated web applications easier. Add this line to the import statements in lib/helpers.py:

from routes import url_for

You can now test the form by visiting http://localhost:5000/page/new.

When the user clicks the Create Page button, the information they enter is submitted to the create() action, so you need to write that next.

create()

The create() action needs to perform the following tasks:

Validate the form

Redisplay it with error messages if any data is invalid

Add the valid data to the database

Redirect the user to the newly created page

Let’s start by creating a FormEncode schema to validate the data submitted. You need to import formencode at the top of the page controller and then import htmlfill, which will be used by the edit() method later in the chapter:

import formencode from formencode import htmlfill

Next define the schema, which looks like this:

class NewPageForm(formencode.Schema):

allow_extra_fields = True

filter_extra_fields = True

content = formencode.validators.String(

not_empty=True,

messages={

'empty':'Please enter some content for the page.'

}

)

heading = formencode.validators.String()

title = formencode.validators.String(not_empty=True)

Setting the allow_extra_fields and filter_extra_fields options to True means that FormEncode won’t raise Invalid exceptions for fields such as the Create Page button, which aren’t listed in the schema, but will filter them out so that they don’t affect the results.

You’ll notice that title and content are required fields because they have not_empty=True specified. You’ll also notice that the content field has a customized error message so that if no text is entered, the error Please enter some content for the page. will be displayed. Notice also that although you specified not_empty=True in the formencode.validators.String validator, the key corresponding to the message is the string 'empty'. This might catch you out if you expected the key to be 'not_empty'.

To handle the validation and redisplay of the form if there are any errors, you’ll use the @validate decorator you learned about in Chapter 4. This requires another import:

from pylons.decorators import validate

You want it to redisplay the result of calling the new() action if an error occurs, so this is how you use it:

@validate(schema=NewPageForm(), form='new')

def create(self):

...

Calling an action wrapped by @validate using a GET request will bypass the validation and call the action anyway. You need to make sure this doesn’t pose a security risk in your application. You could prevent this by testing whether a GET or a POST is being used in the body of the action. You can determine the request method using request.method, or Pylons provides another decorator called @restrict that you can use.

Let’s use the new decorator and add the body of the action to create the page:

@restrict('POST')

@validate(schema=NewPageForm(), form='new')

def create(self):

# Add the new page to the database

page = model.Page()

for k, v in self.form_result.items():

setattr(page, k, v)

meta.Session.add(page)

meta.Session.commit()

# Issue an HTTP redirect

response.status_int = 302

response.headers['location'] = h.url_for(controller='page',

action='view', id=page.id)

return "Moved temporarily"

You’ll also need another import:

from pylons.decorators.rest import restrict

If the data entered is valid, it will be available in the action as the dictionary self.form_result. Here you’re using a trick where you can iterate over the dictionary and set one of the page attributes for each of the values in the schema. Finally, you save the page to the session and then commit the changes to the database. You don’t need to explicitly call meta.Session.flush() because the Pylons session is set to automatically flush changes when you call meta.Session.commit() (this was the autoflush=True argument to sessionmaker() in the model). Once the page has been flushed and committed, SQLAlchemy assigns it an id, so you use this to redirect the browser to the view() action for the new page using an HTTP redirect.

Issuing an HTTP redirect to the view() action is preferable to simply returning the page because if a user clicks Refresh, it is the view() action that is called again, not the create() action. This avoids the possibility that the user will accidentally add two identical pages by mistake by resubmitting the form.

This can cause other problems; for example, how do you pass information obtained during the call to create() to the view() action called next? Because the two pages are generated in two separate HTTP requests, you need to use a session to store information that can be used across the requests. You’ll learn about this later in the chapter.

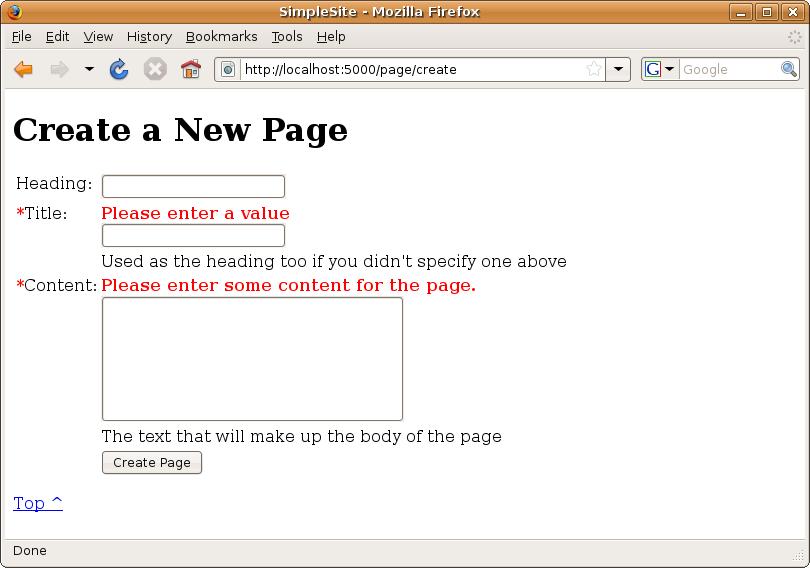

This is a good point to test your new application. If the server isn’t already running, start it with the paster serve --reload development.ini command. Visit http://localhost:5000/page/new, and you should see the form. If you try to submit the form without adding any information, you will see that the validation system repopulates the form with errors.

The errors don’t show up too well, so let’s add some styles. Create the directory public/css, and add the following as main.css:

span.error-message, span.required {

font-weight: bold;

color: #f00;

}

You want to be able to use this style sheet in all the templates, so update the head() def of the /templates/base/index.html base template so that it looks like this:

<%def name="head()">

${h.stylesheet_link(h.url_for('/css/main.css'))}

</%def>

Once again, you’ll need to import the stylesheet_link() helper into your lib/helpers.py file:

from webhelpers.html.tags import stylesheet_link

The helper takes any number of URLs as input and generates link tags for each. Any keyword arguments are added as attributes to each tag. For example:

>>> print stylesheet_link('style.css', 'main.css', media="print")

<link href="/stylesheets/style.css" media="print" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" />

<link href="/stylesheets/main.css" media="print" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" />

You should find that all the error messages appear in red, which will make any mistakes much more obvious to your users (see Figure 8-4). Why not go ahead and create a test page? If you enter any characters such as <, >, or &, you will find they are correctly escaped by Mako because they haven’t been created as HTML literals. This means you can be confident that users of your application can’t embed HTML into the page that could pose a cross-site scripting (XSS) attack risk, as explained in Chapter 4.

If you save the page with valid data, you’ll see you are correctly redirected to the page you have created at the URL http://localhost:5000/page/view/2.

edit() and save()

Now that you’ve implemented the code to create new pages, let’s look at the very similar code required to edit them. Once again, you’ll have an action to display the form (in this case edit()) and an action to handle saving the code (in this case save()). The edit() action will need to load the data for the page from the model and then populate the form with the page information. Here’s what it looks like:

def edit(self, id=None):

if id is None:

abort(404)

page_q = meta.Session.query(model.Page)

page = page_q.filter_by(id=id).first()

if page is None:

abort(404)

values = {

'title': page.title,

'heading': page.heading,

'content': page.content

}

c.title = page.title

return htmlfill.render(render('/derived/page/edit.html'), values)

Notice how this example uses FormEncode’s htmlfill module to populate the form fields with the values obtained from the page object. The call to render('/derived/page/edit.html') generates the HTML, and the call to htmlfill.render() populates the values.

The /derived/page/edit.html template can also use the same fields you used in the new.html template. It looks very similar:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html" />

<%namespace file="fields.html" name="fields" import="*"/>

<%def name="heading()">

<h1 class="main">Editing ${c.title}</h1>

</%def>

<p>Editing the source code for the ${c.title} page:</p>

${h.form_start(h.url_for(controller='page', action='save',

id=request.urlvars['id']), method="post")}

${fields.body()}

${h.field(field=h.submit(value="Save Changes", name='submit'))}

${h.form_end()}

The only difference is that the form action points to save instead of new.

The save() action is also slightly different from the create() action because it has to update attributes on an existing page object. Here’s how it looks:

@restrict('POST')

@validate(schema=NewPageForm(), form='edit')

def save(self, id=None):

page_q = meta.Session.query(model.Page)

page = page_q.filter_by(id=id).first()

if page is None:

abort(404)

for k,v in self.form_result.items():

if getattr(page, k) != v:

setattr(page, k, v)

meta.Session.commit()

# Issue an HTTP redirect

response.status_int = 302

response.headers['location'] = h.url_for(controller='page', action='view',

id=page.id)

return "Moved temporarily"

Notice how this time attributes of the page are set only if they have changed. Remember when using FormEncode in this way, when the form is valid, the converted results get saved as the self.form_result dictionary, so you should get the submitted content from there rather than from request.params. Also, in this instance, the FormEncode schema for creating a new page is the same as the one needed for editing a page, so you are using NewSchemaForm again in the @validate decorator. Often you will need to use a second schema, though.

Why not try editing a page? For example, to edit the home page, you could visit http://localhost:5000/page/edit/1.

list()

Add the list() action:

def list(self):

c.pages = meta.Session.query(model.Page).all()

return render('/derived/page/list.html')

The list() action simply gets all the pages from the database and displays them. Notice the way you use the template context object c to pass the page data to the template. Create a new file named templates/derived/page/list.html to display the list of pages:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html" />

<%def name="heading()">

<h1 class="main">Page List</h1>

</%def>

<ul id="titles">

% for page in c.pages:

<li>

${page.title} [${h.link_to('visit', h.url_for(controller='page', action='view',

id=page.id))}]

</li>

% endfor

</ul>

The h.link_to() helper is a tool for generating a hyperlink, of course you can also write the <a> tag out yourself if you prefer. To use it add the following import to the end of lib/helpers.py:

from webhelpers.html.tags import link_to

If you visit http://127.0.0.1:5000/page/list, you should see the full titles list, and you should be able to visit each page.

delete()

Users of the application might want to be able to delete a page, so let’s add a delete() action.

Add the following action to the page controller:

def delete(self, id=None):

if id is None:

abort(404)

page_q = meta.Session.query(model.Page)

page = page_q.filter_by(id=id).first()

if page is None:

abort(404)

meta.Session.delete(page)

meta.Session.commit()

return render('/derived/page/deleted.html')

This page searches for the page to be deleted and aborts with a 404 Not Found HTTP status if the page doesn’t exist. Otherwise, the page is deleted using the Session object, and the changes are committed.

Add the templates/derived/page/deleted.html template with the following content to display a message that the page has been deleted:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html" />

<%def name="heading()">

<h1 class="main">Page Deleted</h1>

</%def>

<p>This page has been deleted.</p>

Later in the chapter you’ll see how you can use a session and a flash message to display a simple message like this on a different page rather than needing to create a template for it.

At this point, you have a very simple (yet perfectly functional) web site for creating pages and editing their content. There is clearly more that could be done, though, so now it’s time to turn your attention to other aspects of the SimpleSite application you are creating.

Using Pagination

If you want to display large numbers of items, it isn’t always appropriate to display them all at once. Instead, you should split the data into smaller chunks known as pages (not to be confused with the web site pages I’ve been talking about) and show each page of data one at a time. This is called pagination, and providing an interface for the user to page through the results is the job of a paginator.

As an example, imagine what would happen if lots of people started adding pages to the site. You could quickly get, say, 27 pages, which might be too many to display comfortably in a single list. Instead, you could use a paginator to display the web site pages ten at a time in each page in the paginator. The first page of results would show web site pages 1–10, the second would show 11–20, and the last would display 21–27.

The user also needs some way of navigating through the different pages of results. The Pylons WebHelpers come with a webhelpers.paginate module to make pagination easier, and it provides two solutions to allow the user to navigate the pages of data. The first is called a pager, and it produces an interface like the one shown here. The single arrows take you backward or forward one page of results at a time, and the double arrows take you straight to the first or last page.

<< < 11-20 of 27 > >>

The second navigation tool is called the navigator and produces an interface that looks like this:

[1] [2] [3]

This allows you to click directly on the page of results you want to view.

Let’s update the list() action to use the paginator. First import the paginator module into the page controller:

import webhelpers.paginate as paginate

Then update the list() action to look like this:

def list(self):

records = meta.Session.query(model.Page)

c.paginator = paginate.Page(

records,

page=int(request.params.get('page', 1)),

items_per_page = 10,

)

return render('/derived/page/list.html')

There is also a subtlety in this example which you could easily miss. The paginate.Page class has built-in support for SQLAlchemy so in this case, rather than simply providing the paginator with a standard list of Python objects, we are passing in an SQLAlchemy query object. This allows the paginator to only select the records it needs from the database for the page of results it is displaying.

It is unfortunate that the records you are paginating here are pages when the word page is also used to describe a set of records displayed by the paginator. In this case, the page variable retrieved using request.params is referring to the paginator page, not the id of a page record.

The list.html template also needs updating to use the paginator. Here’s what it looks like:

<%inherit file="/base/index.html" />

<%def name="heading()"><h1>Page List</h1></%def>

<%def name="buildrow(page, odd=True)">

%if odd:

<tr class="odd">

%else:

<tr class="even">

% endif

<td valign="top">

${h.link_to(

page.id,

h.url_for(

controller=u'page',

action='view',

id=unicode(page.id)

)

)}

</td>

<td valign="top">

${page.title}

</td>

<td valign="top">${page.posted.strftime('%c')}</td>

</tr>

</%def>

% if len(c.paginator):

<p>${ c.paginator.pager('$link_first $link_previous $first_item to $last_item of

$item_count $link_next $link_last') }</p>

<table class="paginator"><tr><th>Page ID</th><th>Page Title</th><th>Posted</th></tr>

<% counter=0 %>

% for item in c.paginator:

${buildrow(item, counter%2)}

<% counter += 1 %>

% endfor

</table>

<p>${ c.paginator.pager('~2~') }</p>

% else:

<p>

No pages have yet been created.

<a href="${h.url_for(controller='page', action='new')}">Add one</a>.

</p>

% endif

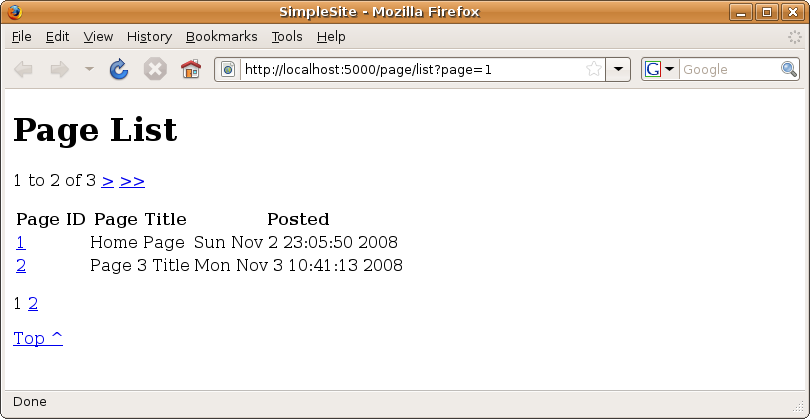

As you can see, the paginator is set up at the bottom of the template, but for each record the buildrow() def is called to generate a representation of the page.

When you click any of the navigation components in the paginator, a new request is made to the list() action with the ID of the paginator page. This is sent via the query string and passed as the page argument to paginate.Page to generate the next set of results.

The nice thing about the Pylons paginator implementation is that it can be used to page any type of information, whether comments in a blog, rows in a table, or entries in an address book. This is because the rendering of each item in the page can be handled in your template so that you have complete control over the visual appearance of your data.

To test the paginator, you might need to create a few extra pages and try setting the items_per_page option to paginate.Page() to a low number such as 2 so that you don’t have to create too many extra pages.

Here are the variables you can use as arguments to .pager() in the template:

- $first_page

Number of first reachable page

- $last_page

Number of last reachable page

- $current_page

Number of currently selected page

- $page_count

Number of reachable pages

- $items_per_page

Maximum number of items per page

- $first_item

Index of first item on the current page

- $last_item

Index of last item on the current page

- $item_count

Total number of items

- $link_first

Link to first page (unless this is the first page)

- $link_last

Link to last page (unless this is the last page)

- $link_previous

Link to previous page (unless this is the first page)

- $link_next

Link to next page (unless this is the last page)

Because these variables look a bit like Mako variables, you might be tempted to think you can put other template markup in the format string to .pager(), but in fact you can use only these variables.

Figure 8-5 shows a page generated with the paginator-enhanced code.

Formatting Dates and Times

To get the date to display in the way it does in the paginator column, you made use of the fact that Python datetime.datetime objects have a strftime() method that turns a date to a string based on the arguments specified. You used %c, which tells the strftime() method to use the locale’s appropriate date and time representation. The display format is highly customizable, though, and takes the options documented in Table 8-1.

Directive |

Meaning |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

%a |

Locale's abbreviated weekday name. |

|

%A |

Locale's full weekday name. |

|

%b |

Locale's abbreviated month name. |

|

%B |

Locale's full month name. |

|

%c |

Locale's appropriate date and time representation. |

|

%d |

Day of the month as a decimal number [01,31]. |

|

%H |

Hour (24-hour clock) as a decimal number [00,23]. |

|

%I |

Hour (12-hour clock) as a decimal number [01,12]. |

|

%j |

Day of the year as a decimal number [001,366]. |

|

%m |

Month as a decimal number [01,12]. |

|

%M |

Minute as a decimal number [00,59]. |

|

%p |

Locale's equivalent of either AM or PM. |

(1) |

%S |

Second as a decimal number [00,61]. |

(2) |

%U |

Week number of the year (Sunday as the first day of the week) as a decimal number [00,53]. All days in a new year preceding the first Sunday are considered to be in week 0. |

(3) |

%w |

Weekday as a decimal number [0(Sunday),6]. |

|

%W |

Week number of the year (Monday as the first day of the week) as a decimal number [00,53]. All days in a new year preceding the first Monday are considered to be in week 0. |

(3) |

%x |

Locale's appropriate date representation. |

|

%X |

Locale's appropriate time representation. |

|

%y |

Year without century as a decimal number [00,99]. |

|

%Y |

Year with century as a decimal number. |

|

%Z |

Time zone name (no characters if no time zone exists). |

|

%% |

A literal '%' character. |

Notes:

When used with the :func:`strptime` function, the %p directive only affects the output hour field if the %I directive is used to parse the hour.

The range really is 0 to 61; this accounts for leap seconds and the (very rare) double leap seconds.

When used with the :func:`strptime` function, %U and %W are only used in calculations when the day of the week and the year are specified.

Table 8-1. Python Date and Time Formatting Directives

Using Sessions and a Flash Message

One of the problems with the setup you have so far is that no notification is displayed to confirm that changes have been successfully saved after you’ve edited a page. As was hinted at earlier in the chapter, you can solve this problem by using Pylons’ session-handling facilities to display a flash message.

Session handling is actually provided in Pylons by the Beaker package set up as middleware, and it can be configured in your development.ini file. By default, session information is stored in a sessions directory within the directory specified by the cache_dir option. This means that by default sessions are stored in your project’s data/sessions directory.

Start by importing the session object into the page controller:

from pylons import session

The session object exposes a dictionary-like interface that allows you to attach any Python object that can be pickled (see http://docs.python.org/lib/module-pickle.html) as a value against a named key. After a call to session.save(), the session information is saved, and a cookie is automatically set. On subsequent requests, the Beaker middleware can read the session cookie, and you can then access the value against the named key.

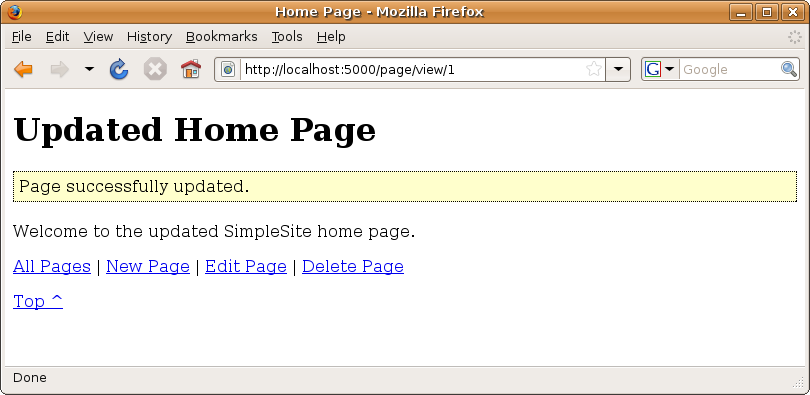

In the save() action, you simply need to add the following lines before the redirect at the end of the action:

session['flash'] = 'Page successfully updated.' session.save()

Now the message will be saved to the flash key. Then in the base template, you’ll need some code to look up the flash key and display the message if one exists. Add the following to the end of templates/base/index.html:

<%def name="flash()">

% if session.has_key('flash'):

<div id="flash"><p>${session.get('flash')}</p></div>

<%

del session['flash']

session.save()

%>

% endif

</%def>

Now add this in the same template before the call to ${next.body()}:

${self.flash()}

Let’s also add some style so the message is properly highlighted. Add this to the public/css/main.css file:

#flash {

background: #ffc;

padding: 5px;

border: 1px dotted #000;

margin-bottom: 20px;

}

#flash p { margin: 0px; padding: 0px; }

Now when the save() action is called, the message is saved in the session so that when the browser is redirected to the view() page, the message can be read back and displayed on the screen.

Give it a go by editing and saving a page (see Figure 8-6).

You can find more information about Pylons sessions at http://docs.pylonshq.com/sessions.html.

Summary

That’s it! You have created a very simple working web page editor. Now, although the site so far does everything you set out for it to do and forms a very good basis for any application you might create yourself, you’ll probably agree it isn’t overly exciting. In the rest of the book, you’ll change that by adding a comment system, a tagging facility, a navigation hierarchy, a hint of Ajax, and a set of navigation widgets. By the end of the book, you’ll have a template project that will serve very well as a basis for many of your own projects, and you will understand many of the key principles you will need to write your own Pylons applications.